My friend Lee recently attended a wedding held at a château outside the town of Sarzeau in Brittany, France. Her description of how she traveled there got me curious, so I went online to look at maps of the area. And as I zoomed in, I noticed a strange-looking peninsula north of the town. As I compared different maps, I discovered that Google, Bing, and Apple all disagreed on the shape of the peninsula, and even on how much of it was really land at all.

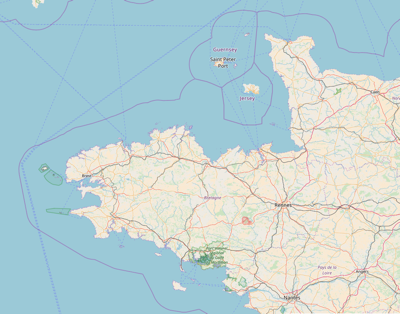

But before we get into those details, let’s get oriented. I’ve used Open Street Maps to give a general geographic overview of where we are—first, here’s Brittany, on the northwest corner of France, right below Normandy (the smaller peninsula at the top):

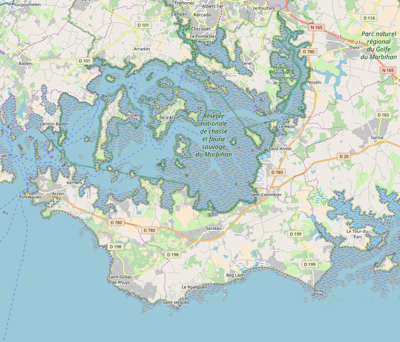

Now let’s zoom in on the area with our mystery peninsula. Sarzeau is located in the middle of the Rhuys Peninsula, about where it says Parc National régional du Golfe du Morbihon on the first map:

You see all those grayish areas with horizontal dashes in them? According to the Open Street Maps key, that pattern represents “Wetland (generic)”. The EPA’s definition of wetlands is “areas where water covers the soil, or is present either at or near the surface of the soil all year or for varying periods of time during the year.” In other words, it’s not always clear whether they’re water or land (and the answer can vary with the seasons, tides, weather, and so on). And that kind of uncertainty and variability poses a challenge for maps.

On to our mystery peninsula—that little protuberance right above the town name, the Presqu’île de Truscat (Truscat Peninsula). Here are the satellite views from Google Maps, Apple Maps (note: this link won’t work unless you have the Maps app), and Bing Maps, with Levels tweaked a little bit to heighten the contrast:

They all look pretty much the same, right? Apple Maps even labels a water feature, Calzac Pond, within the edges of the peninsula. Look closely at the areas surrounding the peninsula, though, and you’ll notice trails that look like streams within the “open water.” They’re examples of that uncertainty we talked about before—where exactly does the land end and the water begin?

The three mapping services disagree wildly on that question. First, Google’s version:

This map has apparently decided that Calzac Pond is actually open to the water on the west, leaving only a narrow strip of land connecting the tip of the peninsula to the mainland. The satellite views show something there, though, that looks different from the other water areas. Is it land? Well, it’s land enough that Open Street Maps offers it as a cycling route:

Okay, then what does Apple Maps think?

This rendering reminds me of Cecilia Gimenez’s “restoration” of the face of Jesus—I have no idea why it’s so crude, just straight lines and angles like a polygonal rendering in an old video game. (This is also the way it looks in an online Michelin map, whose data is supplied by TomTom, as Apple’s is. I guess we can blame TomTom.) And it does seem to have discovered whole new body of water, fairly large but unnamed. None of that makes it less accurate than Google’s, though, as long as the land shown west of Calzac Pond is actually terra firma.

To my eye, Bing Maps most closely represents the peninsula’s shape and balance of land to water as compared to the satellite views:

But whether that makes it the most accurate all depends on how wet those wetlands are. If you rely on Bing Maps or Apple Maps to plan a nice hike to the tip of the peninsula, you might find yourself up to your knees in marsh. On the other hand, Google Maps might convince you it’s basically inaccessible, and you could miss some spectacular birdwatching.

Probably Open Street Maps expresses the uncertainty best. I think its key calls the kind of dashes marking the cycling route “Track. Even amount of solid and soft materials.” That wording covers a lot of ground, you might say, and could serve as a warning that they don’t really know what you’ll find.